Index

This topic area covers statistics and information relating to air pollution in Hull including local strategic need and service provision. Further information is also available about Hull and the environment can be found under Geographical Area within Place, and under Climate Change within Health and Wellbeing Influences.

This page contains information from the Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips. Information is taken ‘live’ from the site so uses the latest available data from Fingertips and displays it on this page. As a result, some comments on this page may relate to an earlier period of time until this page is next updated (see review dates at the end of this page).

Headlines

- Humans interact with the environment constantly. These interactions affect quality of life, years of healthy life lived, and health disparities.

- One measure of air pollution is particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns (PM2.5) and this is estimated to be 7.2 µg/m3 (annual estimate) for Hull for 2023 which is among the second in the Yorkshire and Humber region.

- For 2023, it is estimated that around 5.4% of all deaths among those aged 30+ years are attributable to air pollution in Hull.

- The air pollution levels for particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns and the percentage of all deaths attributable to air pollution among people aged 30+ years for 2023 are the same as they were in 2020.

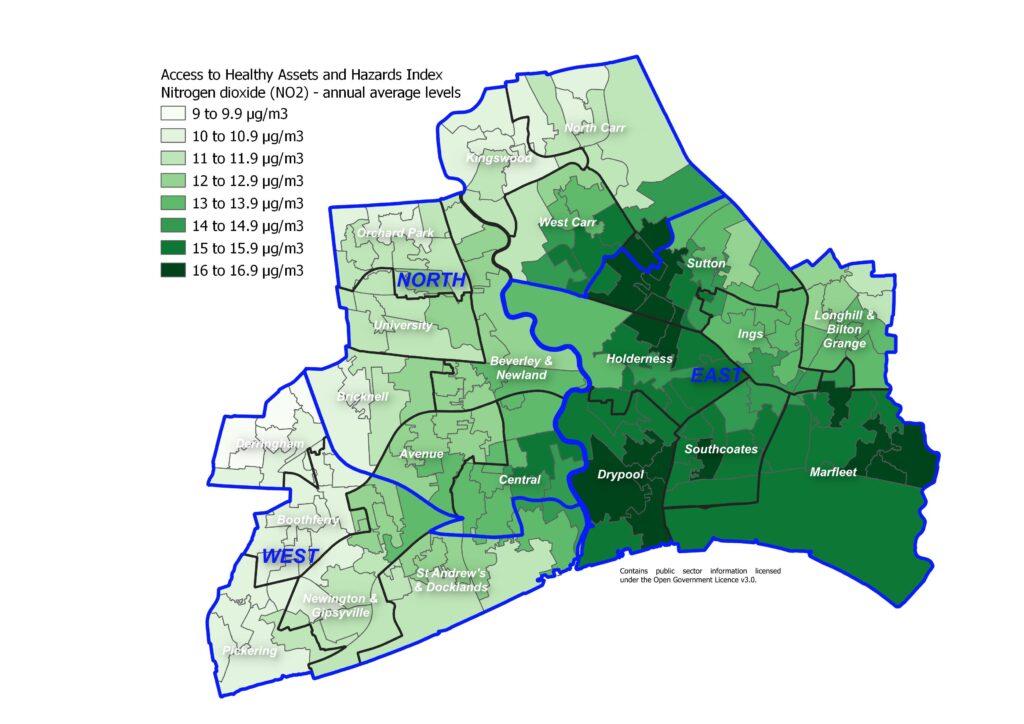

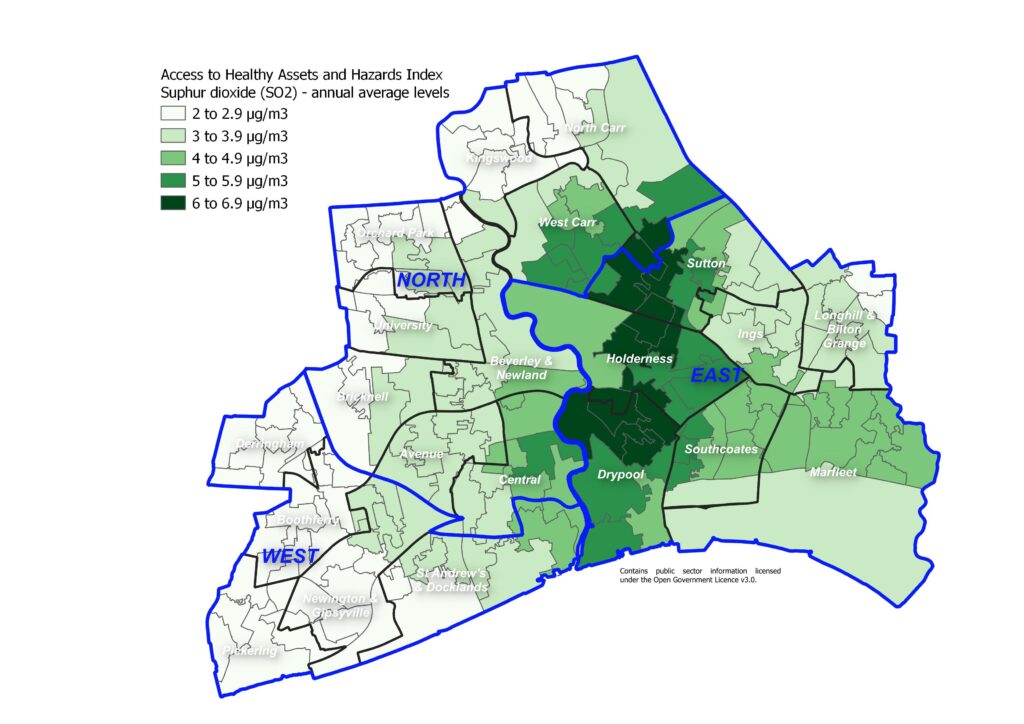

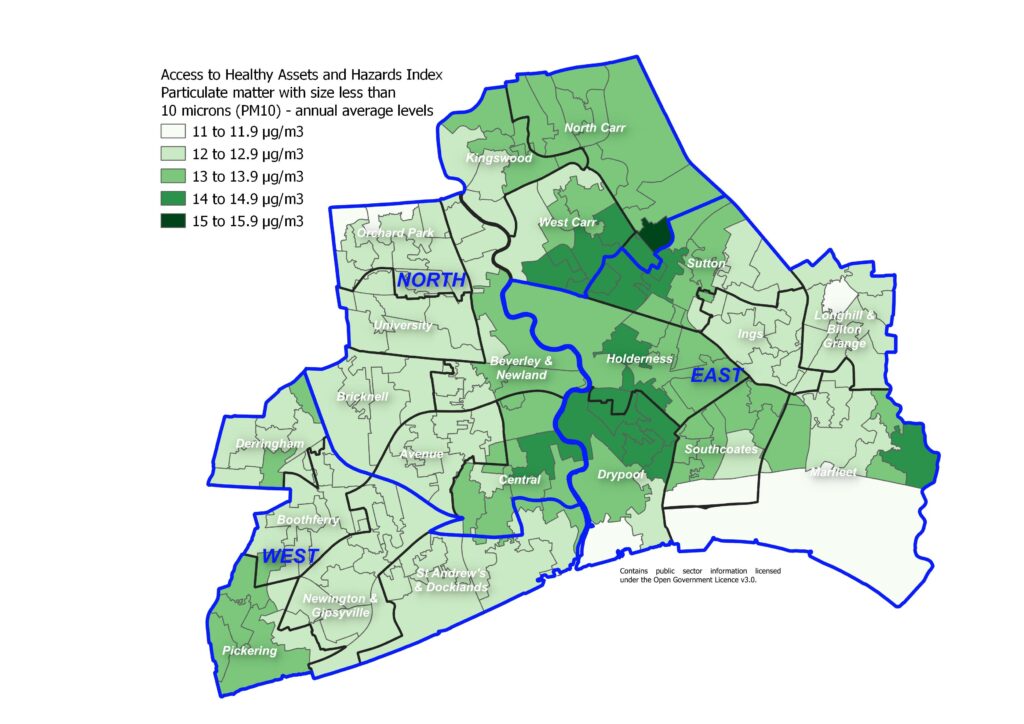

- Based on the Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards Index, the east of the city has the highest levels of nitrogen dioxide with levels particularly high in parts of Drypool, Sutton and Marfleet wards with rates much lower along the wards along the west edge of the Hull boundary. Based on the same index, levels of sulphur dioxide are highest along parts of Drypool, Holderness and Sutton wards along the course of the River Hull, and again the wards along the west edge of the Hull boundary have much lower levels of pollution. Based on the index, levels of particulate matter smaller than 10 microns (PM10) are high in parts of Central, Drypool, Holderness, Marfleet, Sutton and West Carr wards, but the highest levels are in North Carr ward. The lowest levels are the the far east of the city and towards the west boundary although parts of Pickering, Boothferry and Derringham have intermediate levels and it is the wards from north to south from Orchard Park towards Newington & Gipsyville and St Andrew’s & Docklands which also have the lowest levels.

- There is the potential for measures introduced to resolve one environmental problem to be detrimental to other strategies, so full consultation and engagement between the different areas and an assessment of the impacts of any council actions is essential to ensure strategies complement each other.

The Population Affected – Why Is It Important?

Air quality is the term used to describe how polluted the air we breathe is. When air quality is poor, pollutants in the air may be hazardous to people, particularly those with lung or heart conditions. There are a number of different components to air pollution, and monitoring of air quality involves measuring the atmospheric concentrations of a number of particulates and gases. However, people are not only exposed to air pollution outside the home but inside the home too. It is difficult to measure exposure to air pollution at an individual level as it depends on many factors as they are dependent on levels of emissions, the formation of pollutants, weather, topography and the environment. Household chemicals, pets and pests, temperatures, radon, microbes, particulate matter, humidity and ventilation can all influence indoor pollutants.

The UK’s air quality strategy details how the UK aims to achieve prescribed standards and objectives for a suite of air quality concentrations to protect health and the environment. These include nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulphur dioxide (SO2) and particulate matter smaller than 10 microns (PM10), with an additional requirement for particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns (PM2.5). Measurements are usually given as micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m3).

As people are generally more affected by one pollutant than another, locally it is felt that presenting the values of the individual pollutants rather than the Air Pollution Index (API) enables people to make more informed personal decisions. The NHS have summarised some research on lung cancer and heart failure in relation to air pollution. For a lung cancer study, each 10μg/m3 increase in PM10 led to a corresponding increase in the hazard ratio of lung cancer incidence of 1.22 (95% confidence interval 1.03 to 1.45) with no association found between lung cancer incidence and PM2.5, mono nitrogen oxide and nitrogen dioxide combined, or nitrogen dioxide. The heart failure study found an increased risk of heart failure hospitalisation or death for increases in carbon monoxide (3.5% increase in risk per increase of one part per million of pollutant), sulphur dioxide (2.4%), nitrogen dioxide (1.7%), PM2.5 (2.1%) and PM10 (1.6%). In both studies, some potential confounders were included in the model, but it is possible important confounders were not included.

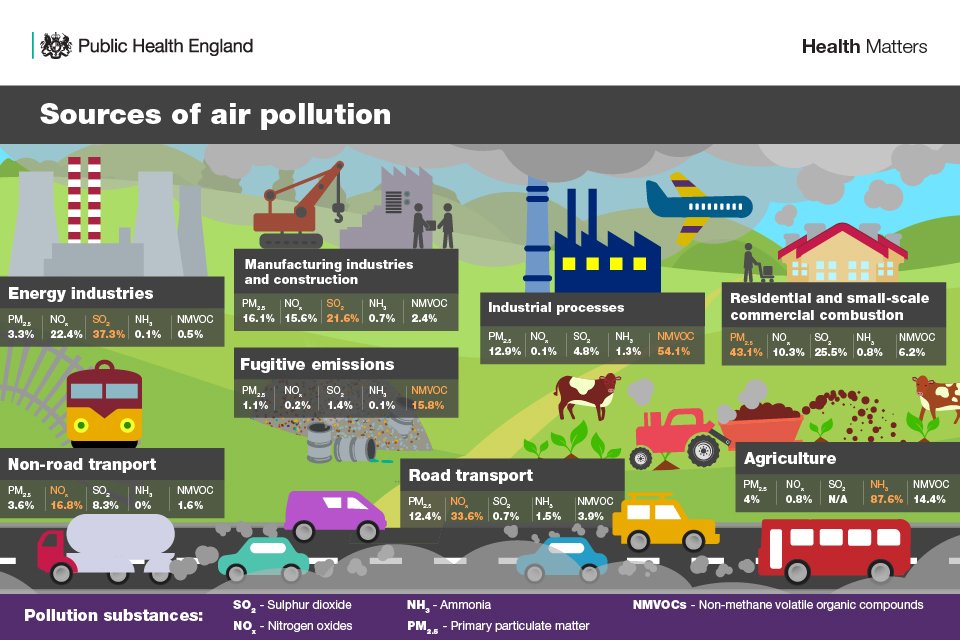

Different factors influence different pollutants in relation to air pollution as illustrate by Health Matters from the Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (formerly Public Health England).

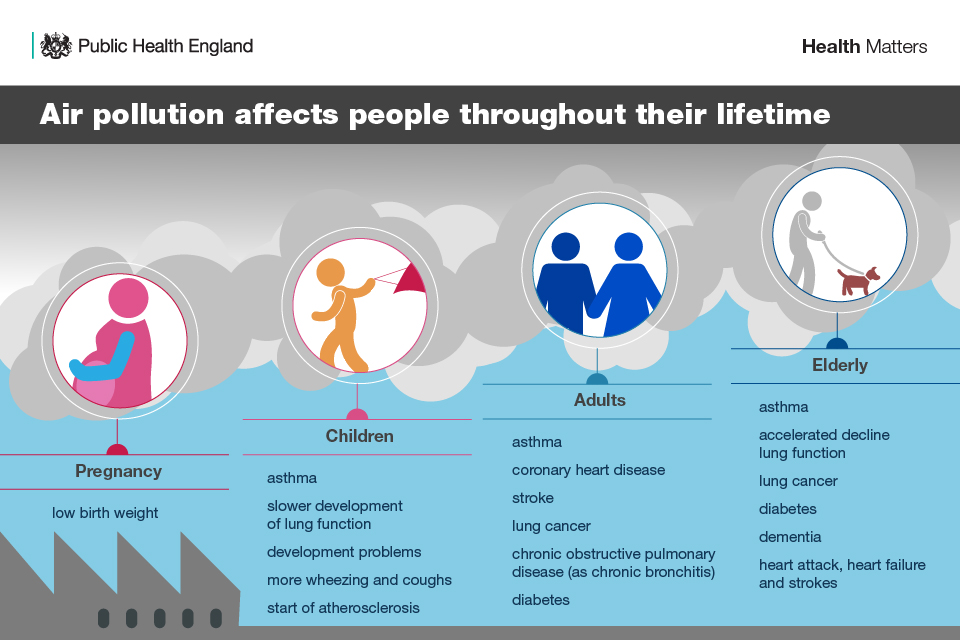

Air pollution affects individuals throughout their entire lifetime.

The Hull Picture

Air Quality in Hull

Hull City Council has a very good story to tell regarding air quality so far, and it measures air quality across the city, with results used to inform planning policy and applications as well as the Action Plan Measures in the Council’s Air Quality Strategy and an Annual Status Reports (ASR) which is sent to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs’ (DEFRA). Levels of mono nitrogen oxide, nitrogen dioxide, mono nitrogen oxide and nitrogen dioxide combined, sulphur dioxide, PM10 and PM2.5 are all measured.

Air quality in Hull is better than most areas of a similar nature, and is generally improving, with only one area exceeding the air quality objectives. This is an area close to the A63, and the road improvements that are ongoing are designed to remove this exceedance. The Council’s Air Quality Strategy aims to ensure that existing levels do not increase, and are reduced further wherever possible. The highest pollution concentrations are along the south edge of Hull (A63), near the train/bus station, and near the industrial areas (up the centre of Hull from South to North approximately route of river and the A1033) and around the Docks (in South-East corner (Marfleet ward) of Hull), although as mentioned only an area around the A63 exceeds the National Air Quality Objectives.

The annual concentration of fine particulate matter (PM2.5 ) at an area level, adjusted to account for population exposure is given on Fingertips. Whilst the estimate of PM2.5 is lower in Hull than England, it is among the highest across the region for 2023.

Compared with benchmark

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | Craven | Hambleton | Harrogate | Richmondshire | Ryedale | Scarborough | Selby | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Air pollution: fine particulate matter (new method - concentrations of total PM2.5) (Not applicable Not applicable) | 2023 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 5.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6.9 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 7.1 |

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | Craven | Hambleton | Harrogate | Richmondshire | Ryedale | Scarborough | Selby | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Air pollution: fine particulate matter (new method - concentrations of total PM2.5) (Not applicable Not applicable) | 2023 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 5.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6.9 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 7.1 |

The estimate of PM2.5 in Hull has decreased between 2018 and 2020 in line with decreases seen regionally and for England, although the decrease has been slightly greater in Hull. There was a slight decrease between 2018 and 2019, and it is likely that the greater decrease between 2019 and 2020 could be associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. There has been some variability since 2020, but the estimate for 2023 at 7.2 µg/m3 is the same as it was for 2020.

Compared with benchmark

Air pollution: fine particulate matter (new method - concentrations of total PM2.5) (Not applicable Not applicable)

|

Period

|

Kingston upon Hull |

Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical)

|

England

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Count

|

Value

|

95%

Lower CI |

95%

Upper CI |

||||

| 2018 | • | - | 9.8 | - | - | 8.2 | 9.5 |

| 2019 | • | - | 9.6 | - | - | 8.9 | 9.6 |

| 2020 | • | - | 7.2 | - | - | 6.6 | 7.5 |

| 2021 | • | - | 7.6 | - | - | 6.7 | 7.4 |

| 2022 | • | - | 7.5 | - | - | 6.8 | 7.8 |

| 2023 | • | - | 7.2 | - | - | 6.8 | 7.0 |

Source: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

The Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards which includes air pollution levels and was updated in 2024.

The Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards (AHAH) index is designed to allow policy and decision makers to understand which areas have poor environments for health, and to help move away from treating features of the environment in isolation.

The Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards index is comprised of four domains: access to retail services (fast food outlets, gambling outlets, pubs/bars/nightclubs, off licences, tobacconists), access to health services (GP surgeries, A&E hospitals, pharmacies, dentists and leisure centres), the physical environment (green and blue spaces) and levels of air pollution (nitrogen dioxide (NO2), particulate matter smaller than 10 microns (PM10) and sulphur dioxide (SO2)).

In 2024, the Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards Index is very high in Hull with 44.7% of Hull’s population residing in the bottom fifth of areas nationally in relation to the Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards Index. The percentage nationally is 20.9% and across the other 14 lower tier local authorities in the region the range is from 1.3% to 32.6%.

Compared with benchmark

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | North Yorkshire UA | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Access to Healthy Assets & Hazards Index (Persons All ages) | 2024 | 20.9 | 18.2 | 44.7 | 9.4 | 23.6 | 10.7 | 1.3 | 13.4 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 9.7 | 13.7 | 32.6 | 5.1 | 13.1 | 30.3 | 18.8 |

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | North Yorkshire UA | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Access to Healthy Assets & Hazards Index (Persons All ages) | 2024 | 20.9 | 18.2 | 44.7 | 9.4 | 23.6 | 10.7 | 1.3 | 13.4 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 9.7 | 13.7 | 32.6 | 5.1 | 13.1 | 30.3 | 18.8 |

Despite the very high levels in Hull, the index has decreased considerably since 2016 when nine in ten residents lived in the worst fifth of areas of England in relation to the index, although there was a large decrease between 2016 and 2017 to 46% with only relatively minor changes to 2022 and 2023.

In 2024, it is estimated that 120,220 residents in Hull live within areas defined as the bottom fifth of areas nationally based on the Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards Index.

Compared with benchmark

Access to Healthy Assets & Hazards Index (Persons All ages)

|

Period

|

Kingston upon Hull |

Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical)

|

England

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Count

|

Value

|

95%

Lower CI |

95%

Upper CI |

||||

| 2016 | • | 233157 | 90.0% | - | - | 22.2% | 21.2% |

| 2017 | • | 120814 | 46.3% | - | - | 14.1% | 21.1% |

| 2022 | • | 114694 | 44.3% | - | - | 19.9% | 22.6% |

| 2024 | • | 120220 | 44.7% | - | - | 18.2% | 20.9% |

Source: Consumer Data Research Centre

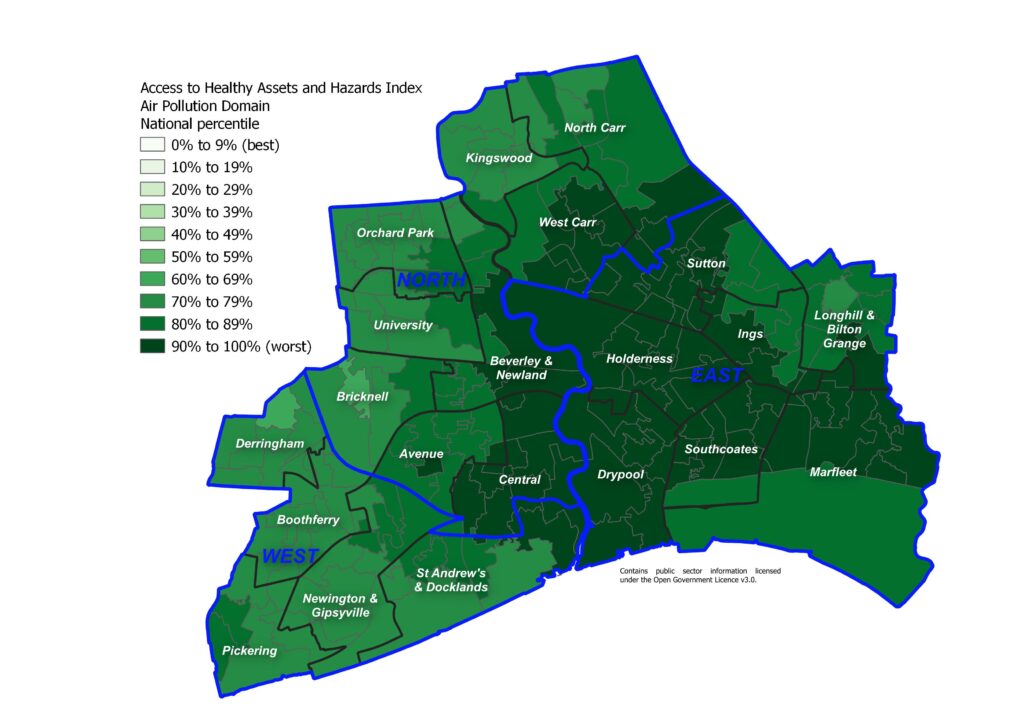

Information relating to version 4 of the Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards index is available at lower layer super output area geographical level. There are 33,755 lower layer super output areas in England, and the percentile score has been calculated for each of the 168 lower layer super output areas in Hull. The index was updated in July 2024, and information on the individual components is available. The air pollution data is from the Department for Environment, Farming and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) for 2022.

Levels of air pollution tend to be higher along main arterial travel routes and in areas with higher levels of industry and this is the case for Hull. Furthermore, as the prevailing wind in the UK is predominantly from the south-west, this generally means that air pollution levels tend to be higher in easterly areas.

The following map illustrates the average annual levels of sulphur dioxide. There appears to be two pockets of areas with relatively high levels of sulphur dioxide in Hull and areas further away from these two areas tending to have the lowest levels compared to the Hull average.

The following map illustrates the average annual levels of particulate matter with size less than 10 microns.

The levels of air pollution in terms of average annual levels of nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide and particulate matter with size less than 10 microns are high relative to other areas of England. This is not particularly surprising as most cities with relatively high density of roads and industry compared to rural areas will tend to have relatively high levels of air pollution. Not surprisingly, the areas with the highest levels of pollution are those with the higher levels of industry and in the east where the prevailing wind will tend to increase levels of air pollution.

The percentile scores range from 68 to 100 so none of Hull’s 168 lower layer super output areas are the the best 60% nationally in terms of air pollution levels. Four in ten of Hull’s lower layer super output areas are in the worst 10% of areas of England in terms air pollution levels, and almost seven in ten of the areas are in the worst 20% nationally. All but two of Hull’s 168 lower layer super output areas are in the worst 30% of areas nationally in terms of air pollution.

Estimated Mortality Attributable to Air Pollution

The Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants (COMEAP) estimated that if all man-made particulate pollution were removed, this would lead to an increase in life expectancy of around 6 months although the effect could be as small as one month and as large as a year. To put this into context, the effect on life expectancy of continued smoking is seven years on average. The Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips previously presented the percentage of deaths among those aged 30+ years attributable to air pollution. However, DEFRA’s model for Hull was found to be inaccurate, and as a result it is possible that the percentages of deaths based on these levels of air pollution may also be inaccurate.

More recently, the Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ have used a new method to calculate the fraction of annual all cause adult mortality attributable to particulate air pollution (PM2.5). It represents the mortality burden associated with long-term exposure to particulate air pollution at current levels, expressed as a percentage of annual deaths from all causes in those aged 30+ years.

From COMPEAP (2022), a 10 µg/m3 increased in PM2.5 equates to a relative risk of 1.08 (i.e. an 8% risk), and using this information a population weighted modelled annual average background PM2.5 concentration x, RR is calculated as (1.08)(x/10) (from Public Health England, 2014). The ‘attributable fraction’ of deaths or fraction of deaths attributable to PM2.5 is expressed as a percentage, calculated as 100*(RR-1)/RR.

Population weighted annual average concentrations of PM2.5 were provided by Ricardo Energy and Environment for all lower tier and unitary local authorities within England, as well as combined at upper tier, regional and national level.

Thus with a estimate of 7.2 µg/m3 for PM2.5 for 2023 above, the relative risk for Hull would be 1.080.72 which is 1.057, and the attributable fraction would be 100*(RR-1)/RR or 100*0.057/1.057 or 5.7, i.e. 5.4% for the fractions of deaths attributable to PM2.5 in Hull for 2023.

The fraction of deaths attributable to air pollution at 5.4% is among the highest in the region.

Compared with benchmark

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | North Yorkshire UA | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Air pollution: estimated fraction of mortality attributable to particulate air pollution (Persons 30+ yrs) | 2023 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.3 |

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | North Yorkshire UA | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Air pollution: estimated fraction of mortality attributable to particulate air pollution (Persons 30+ yrs) | 2023 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.3 |

The percentage of deaths attributable to PM2.5 in Hull has decreased from 2018 and 2019 when it was over 7% to 5.4% in 2020. The percentage increased to 5.7% in 2021, but has subsequently fallen to 5.4% for 2023 which is the same as it was for 2020.

Compared with benchmark

Air pollution: estimated fraction of mortality attributable to particulate air pollution (Persons 30+ yrs)

|

Period

|

Kingston upon Hull |

Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical)

|

England

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Count

|

Value

|

95%

Lower CI |

95%

Upper CI |

||||

| 2018 | • | - | 7.2% | - | - | 6.1% | 7.1% |

| 2019 | • | - | 7.1% | - | - | 6.6% | 7.1% |

| 2020 | • | - | 5.4% | - | - | 5.0% | 5.6% |

| 2021 | • | - | 5.7% | - | - | 5.0% | 5.5% |

| 2022 | • | - | 5.6% | - | - | 5.1% | 5.8% |

| 2023 | • | - | 5.4% | - | - | 5.1% | 5.2% |

Source: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

The impact of air pollution on health will not affect everyone the same, and it is likely that people living in more deprived areas who are more likely to have more ill health and comorbidities are more likely to be affected by poor air quality compared to people living in less deprived areas. Housing conditions may also be worse in more deprived areas which could impact on indoor air pollution levels.

Strategic Need and Service Provision

Hull’s improving year on year trend relating to air quality has been maintained with the Council’s Air Quality Strategy, and an increase in background levels are prevented. Continuing to raise awareness of the health and financial benefits of good air quality is a key measure in encouraging behaviour change and less polluting lifestyle choices.

It is necessary to work together to maintain and expand an environment that promotes active travel for all ages in order to reduce the impact on air pollution from cars. Food production also has a substantial impact on air pollution, particularly meat and manufactured food products. Raising awareness of this and encouraging people to buy locally produced food could all help to reduce air pollution levels.

It is important that any measures in the proposed climate change strategy and proposed action plan consider the implications on and as far as possible complement those in the Air Quality Strategy, as some could have a detrimental impact on air quality. For example, monitoring during the COVID-19 lockdown indicates that as direct emissions from vehicles decrease (mono nitrogen oxide and nitrogen dioxide combined) it has the potential to result in an increase in the concentrations of other potentially harmful gases, such as ozone, and only a minimal reduction in the emissions of particulate matter. This has implications and will need to be considered when advocating a change to electric vehicles.

An Air Pollution Needs Assessment is currently underway with the aim of providing local information relating to air pollution and the impact on health and wellbeing.

Resources

HM Government, The Clean Growth Strategy: Leading the way to a low carbon future. 2017, HM Government: London.

Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/

Public Health England (now Office for Health Improvement & Disparities). Estimating local mortality burdens associated with particulate air pollution, 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/particulate-air-pollution-quantifying-effects-on-mortality

Hull 2020 Carbon Neutral Strategy. Hull City Council, 2020. http://www.hull.gov.uk/environment/pollution/hull-2030-carbon-neutral-strategy

Updates

This page was last updated / checked on 7 February 2025.

This page is due to be updated / checked in July 2025.