Index

This topic area covers statistics and information relating to diet and nutrition among children and young people in Hull including local strategic need and service provision. Further information relating to Diet and Nutrition Among Adults is given under Lifestyle Factors within Adults. Diet information has been collected within Hull’s Health and Wellbeing Surveys and full reports are available under Surveys within Tools and Resources. Further information relating to children eligible for free school meals can be found under Schools, Education and Qualifications and information relating to food insecurity (concerns over being able to provide food for the family) can be found under Financial Resilience both under Health and Wellbeing Influences.

This page contains information from the Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips. Information is taken ‘live’ from the site so uses the latest available data from Fingertips and displays it on this page. As a result, some comments on this page may relate to an earlier period of time until this page is next updated (see review dates at the end of this page).

Headlines

- Children’s dietary behaviour is shaped early in life, with behaviours predominantly learnt from parents, and these behaviours often extend into their adult lives.

- Poor diet has been linked to several types of cancers, and can increase the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease. It also can have an impact on malnutrition, as well as overweight and obesity.

- Eating a balanced diet is important during childhood and is important for children to grow, develop and be healthy. Some nutrients such as iron are important to help with cognition and learning, and calcium is important for healthy strong bones.

- Fewer people in Hull eat five portions of fruit and vegetables (5-A-DAY) and diets are poorer in Hull than England. There is a strong association between 5-A-DAY and both age and deprivation with diets worse among young adults and people living in the most deprived areas.

- High levels of deprivation increase the barriers to a healthy diet, through reduced access to fresh fruit and vegetables, knowledge about diet and cooking, and financial barriers. Hull also has a high number of takeaways.

- Hull has developed a whole-system approach to promoting a healthy weight which considers multi-factorial drivers of overweight and obesity and involves transformative co-ordinated action across a broad range of disciplines and stakeholders. Hull is recognised nationally as a bronze Sustainable Food City, which is led by the Hull Food Partnership.

The Population Affected – Why Is It Important?

Parents are the most influential people in a child’s life, and children will mimic and learn behaviour from their parents including poor dietary behaviours. Children’s food preferences are shaped by early experience with food and eating, and it has been found that children often adopt unhealthy dietary behaviours which extend into their adult lives.

Poor diet has been linked to several types of cancer including cancer of the bowel, stomach, breast, lung, prostate, pancreas, oesophagus and bladder. A diet high in fat and salt is also a risk factor for cardiovascular disease as fatty build-ups within the arteries can cause heart attacks, stroke and other cardiovascular events and salt increases the risk of hypertension which is also a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

In more deprived areas, access to good quality fruit and vegetables, reliance of public transport (which restricts ability to buy heavy fruit and vegetables), cost issues and lack of cookery knowledge and skills are further barriers to eating a well-balanced diet.

In 2005, it was estimated that food related ill health is responsible for about 10% of morbidity and mortality in the UK.

Clearly there are strong associations between diet, physical activity and obesity, but they are also all independent risk factors for poor health. In 2006/07, the cost of the NHS in the UK was estimated to be £5.8 billion for poor diet-related ill health, £0.9 billion for physical inactivity, and £5.1 billion for overweight and obesity. In 2014/15, the estimated costs for overweight and obesity to the NHS had risen to £6.1 billion (with a total cost of £27 billion to the wider society).

In the National Food Strategy: An Independent Review for Government published in 2019, it was stated that the government spends an estimated £18 billion (8% of all government healthcare expenditure) on conditions related to high body mass index every year, and that this was before diet-related disease not linked to weight was taken into account. In 2019/20, there were just over one million hospital admissions where obesity was recorded as the primary or secondary diagnosis – a 17% increase on 2018/19. They state that the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development estimates that the combined costs of conditions related to a high body mass index, in lost workforce productivity, reduction in life expectancy and NHS funds, is £74 billion every year. This is equivalent to cutting the UK’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 3.4%. Again this does not account for cost associated with diet-related disease not linked to weight.

The Hull Picture

2024 Health and Wellbeing Survey

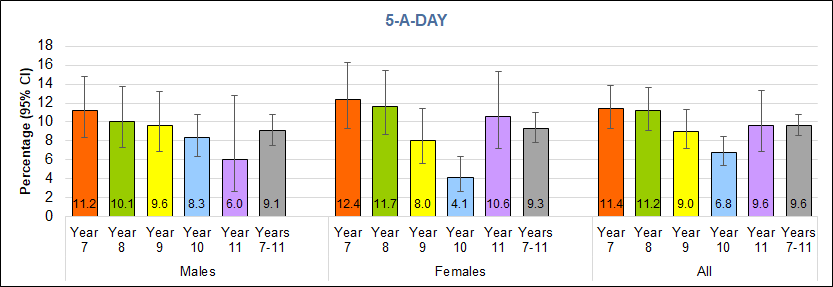

From the local Young People Health and Lifestyle Survey 2024, around one in ten young people overall reported they ate 5-A-DAY fruits and vegetables, with similar percentages in boys and girls. Year 7 pupils (aged 11-12 years) had the highest percentage eating 5-A-DAY, with percentages decreasing as ae increased, with the exception of year 11 girls.

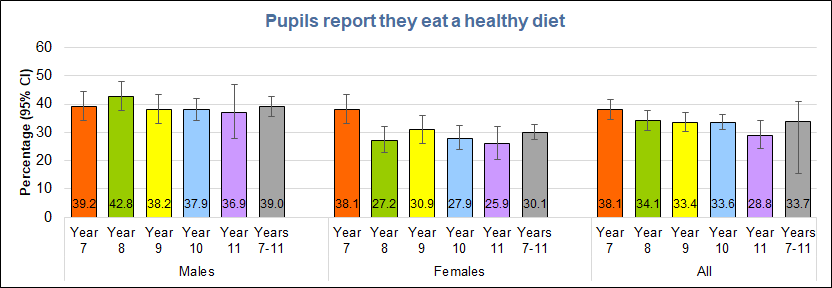

Despite the low percentage of young people reporting eating 5-A-DAY fruits and vegetables, around three times as many reported usually eating a healthy diet (33.7% overall). Among boys, there was little difference by school year, with around four in ten boys reporting they usually eat a healthy diet. Among girls, almost four in ten in year 7 reported usually eating a healthy diet, compared with around one in four girls in other year groups.

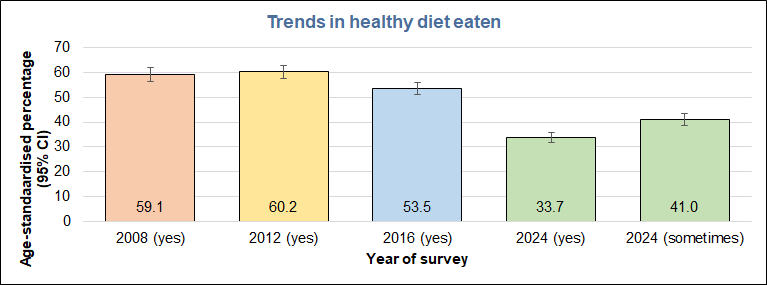

As well as one in three reporting they usually eat a healthy diet, a further four in ten reported they sometimes ate a healthy diet. In previous surveys, the option ‘sometimes’ was not available, so comparisons with earlier surveys are complicated, but between 33.7% and 74.7% ate a healthy diet in the 2004 survey, which compares to between 53% and 60% in previous surveys.

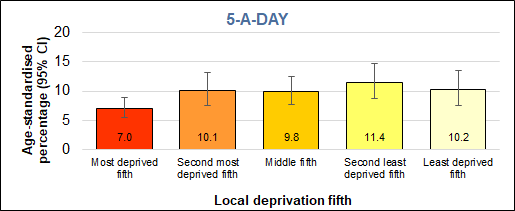

The percentage of young people eating 5-A-DAY varied by deprivation, with 7% of young people living in the most deprived fifth of areas of Hull reporting they ate 5-A-DAY, compared with 10% of young people living in the least deprived fifth of areas of the city.

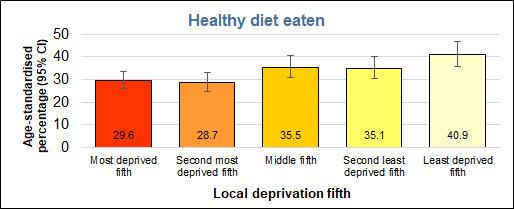

Again, between three times and four times as many young people reported they usually eat a healthy diet than ate 5-A-DAY. A clear trend with deprivation was apparent, with the percentage usually eating a healthy diet increasing from 30% among young people living un the most deprived fifth of areas of Hull to 41% of those living in the least deprived fifth of areas.

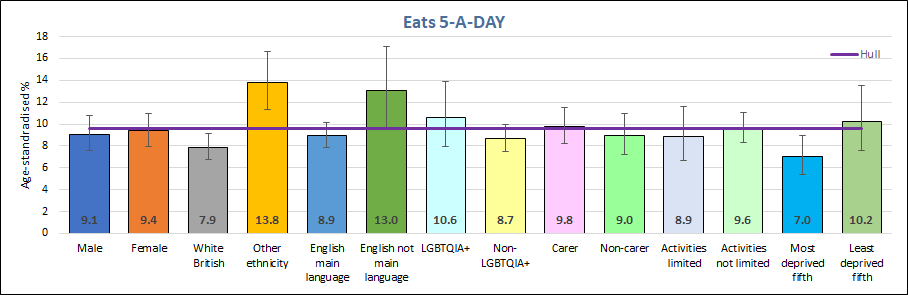

The only subgroup with a percentage eating 5-A-DAY that was significantly higher than the Hull average was young people with minority ethnic heritage, while White British respondents and those living Hull’s most deprived fifth of areas had significantly lower percentages eating 5-A-DAY.

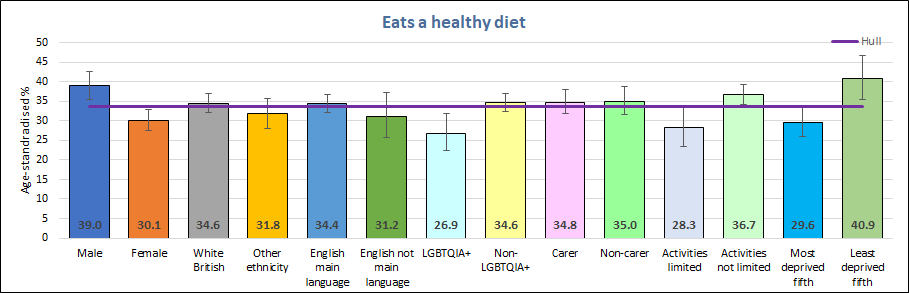

Boys were four times more likely to report usually eating a healthy diet than eating 5-A-DAY, as were those living in the least deprived fifth of areas of Hull, the two subgroups with significantly higher percentages than the Hull average reporting usually eating a healthy diet. Girls and young people identifying as LGBTQ+ were the only two subgroups with lower than average percentages usually eating a healthy diet (three times and two and a half times higher respectively the the percentages eating 5-A-DAY).

National estimates for Hull are conflicting depending on the survey. The Health Survey for England reported that around 20% of secondary school pupils in 2022 ate 5-A-DAY in England, but the Active Lives Survey reported that 52% of 15 year olds in England ate 5-A-DAY in 2014/15 and their estimate for Hull was 44%. The differences in the two national surveys are likely associated with the differences in the questions (with the Health survey for England using a very detailed set of questions) and the interpretation of what constitutes a portion of fruit and vegetables. The Active Lives Survey is reported within the Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips.

Compared with benchmark

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield | North Yorkshire Cty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Percentage who eat 5 portions or more of fruit and veg per day at age 15 (Persons 15 yrs) | 2014/15 | 52.4 | 49.6 | 43.8 | 53.1 | 50.8 | 44.3 | 54.5 | 44.5 | 42.2 | 47.1 | 47.8 | 49.6 | 48.9 | 53.6 | 51.8 | 47.4 | 54.5 |

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield | North Yorkshire Cty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Percentage who eat 5 portions or more of fruit and veg per day at age 15 (Persons 15 yrs) | 2014/15 | 52.4 | 49.6 | 43.8 | 53.1 | 50.8 | 44.3 | 54.5 | 44.5 | 42.2 | 47.1 | 47.8 | 49.6 | 48.9 | 53.6 | 51.8 | 47.4 | 54.5 |

2016 Health and Wellbeing Survey

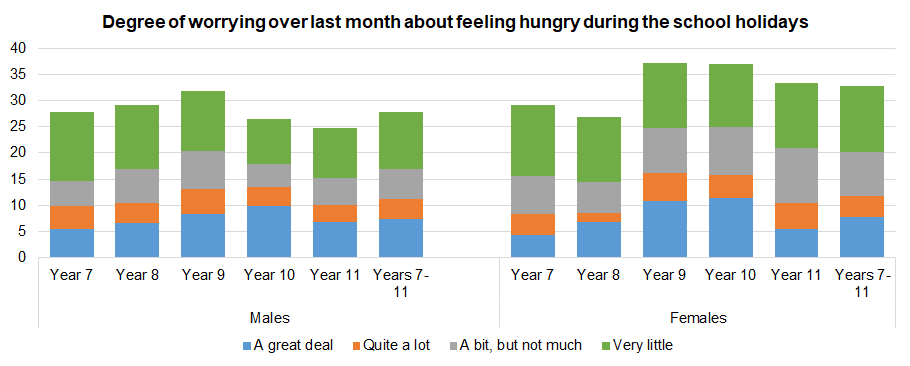

Questions about eating breakfast and worrying about being hungry during school holidays were not asked in the 2024 survey, so this section reports results from these questions from the 2016 survey.

In the local survey, around seven in ten Year 7 and Year 8 pupils stated that they were involved in cookery lessons or cookery in after-school clubs, but this fell to 43% in Year 9, 18% in Year 10 and 11% in Year 11.

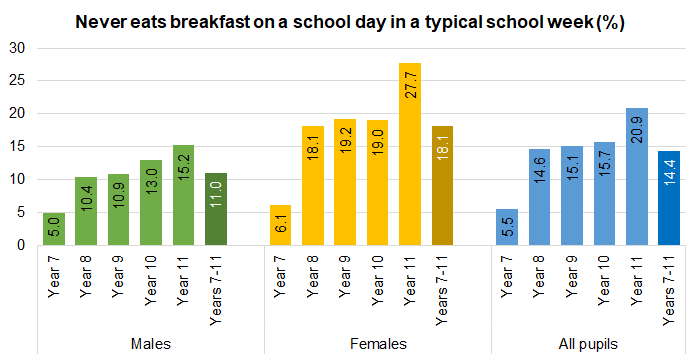

One in twenty Year 7 children never had breakfast on a school day, but this increased to 15% for boys and 28% for girls by Year 11. Children living in the most deprived areas of Hull were the most likely to miss breakfast (16% of boys and 21% of girls living for the most deprived fifth of areas of Hull compared to 8% of boys and 15% of girls living in the least deprived fifth of areas of Hull). In 2008-09, it was estimated that around 10% of boys and 15% of girls missed breakfast, but this has increased 11% of boys and 18% of girls in 2016.

Overall, across all school years, one in nine children worried ‘a great deal’ (7.4% of boys and 7.7% of girls) or ‘quite a lot’ (3.9% of boys and 4.1% of girls) about feeling hungry during school holidays.

Further information relating to children eligible for free school meals can be found under Schools, Education and Qualifications. In the adult Health and Wellbeing Survey 2019, survey responders were asked about their frequency of worrying over not having enough food, and the findings are reported within Financial Resilience under Health and Wellbeing Influences as well as within the full survey report available within Local Surveys Involving Adults under Tools and Resources.

Strategic Need and Service Provision

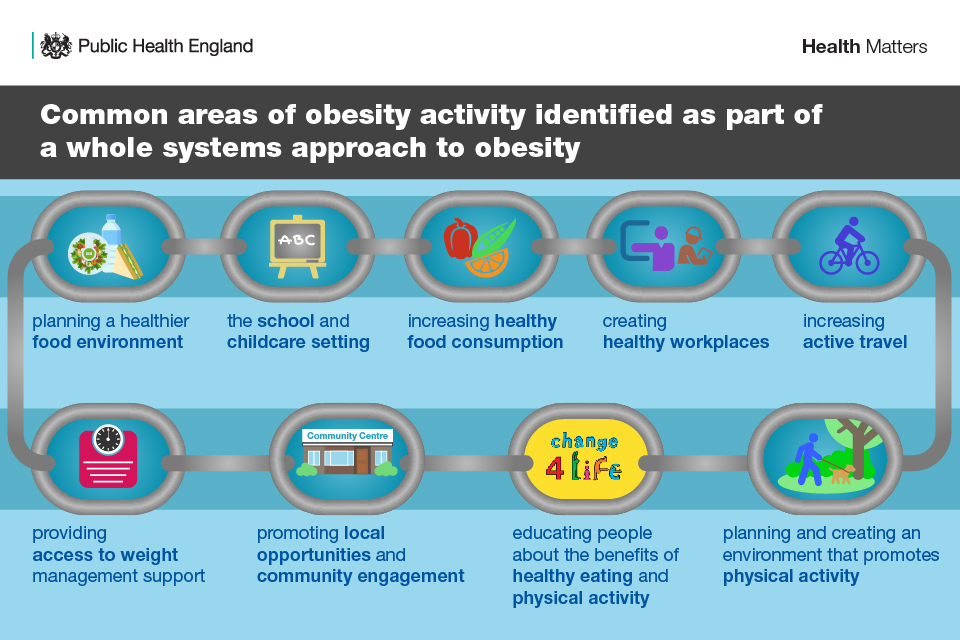

A poor diet needs to be tackled as part of a whole–system, multifaceted approach. The local food environment and availability of food choices affects the types of food that residents can buy and this can be influenced by the Local Plan, which already includes a restriction of new food takeaways within 400 metres of a secondary school or playing field.

The price of food also impacts on diet and working together with the Hull Food Partnership on the Sustainable Food Cities agenda will improve access to healthy and affordable food.

Hull is recognised nationally as a bronze Sustainable Food City and is led locally by the Hull Food Partnership. The actions to achieve the award include:

- Promoting healthy and sustainable food to the public.

- Tackling food poverty, diet related ill-health and access to affordable healthy food.

- Building community food knowledge, skills, resources and projects.

- Promoting a vibrant and diverse sustainable food economy.

- Transforming catering and food procurement.

- Reducing waste and the ecological footprint of the food system.

- Developing a locally adopted Food Charter.

Services such as the Healthy Lifestyle Service provides support to families and their children via the HENRY programme and practical cooking sessions. School Nurses carry out the National Child Measurement Programme – measuring and weighing children in reception and year 6, which helps services to support those families most at need. Interventions such as the Food for Life Programme work locally to change the food culture within schools, from the food provided, learning about nutrition, cooking in the curriculum to growing food.

Supporting national campaigns such as Change for Life and Eat Them to Defeat Them helps to get nutritional messages across in a fun interactive way.

Resources

NHS. Better Health Healthier Families (previously Change4Life). https://www.nhs.uk/healthier-families/

Local Health and Wellbeing Surveys

Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/

Rayer M and Scarborough P. The burden of food related ill health in the UK. J Epidemiol Community Health, 2005;59:1054-1057.

Scarborough P, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe KK, Allender S, Foster C and Rayner M. The economic burden of ill health due to diet, physical activity, smoking, alcohol and obesity in the UK: an update to 2006-07 NHS costs. Journal of Public Health, 2011;33(4):527-535.

Dimbleby H. National Food Strategy: An Independent Review for Government, 2019. https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/the-report/

Updates

This page was last updated / checked on 25 April 2025.

This page is due to be updated / checked in April 2026.