Index

This topic area covers statistics and information relating to oral health among children and young people in Hull including local strategic need and service provision. Further information relating Oral Health Among Adults is given under Lifestyle Factors within Adults.

This page contains information from the Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips. Information is taken ‘live’ from the site so uses the latest available data from Fingertips and displays it on this page. As a result, some comments on this page may relate to an earlier period of time until this page is next updated (see review dates at the end of this page).

Headlines

- Access to routine care and emergency treatment from March 2020 to the end of 2021 was severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. When practices did reopen, they had a backlog of patients requiring care. Furthermore, it is likely that the cost of living crisis has impacted adversely on oral health. From anecdotal evidence, access to dental care can be difficult with a relatively high percentage of people not registered with a dental surgery or on long waiting lists to register with an NHS dental surgery.

- For 2023/24, national statistics quote that 61.5% of under 18s in Hull had attended a dental appointment within the last year (compared to 55.4% for England). However, it is possible that the national figures are misleading as it is based on Hull residents and it is likely that some Hull dentists treat East Riding of Yorkshire residents. It is not known exactly how many East Riding of Yorkshire residents attend Hull dentists, but if the percentages are similar to those registered with Hull GPs (8%) and an adjustment is applied, then it is estimated that around 56.6% of children and young people aged under 18 years living in Hull had attended a dental appointment in the last year. This represents a decrease compared to prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (69.4% from national figures and 63.1% ‘adjusting’ for East Riding of Yorkshire residents compared to 58.4% for England).

- Oral health survey were completed for three year olds in the 2019/20 academic year and among year 6 children (aged 10-11 years) in the 2022/23 academic year. Children in Hull did not participate in the survey, but overall for England, 10.7% of three year olds and 16.2% of year 6 children had evidence of tooth decay. However, half of Hull’s children live in the most deprived areas of England, and there were 16.6% of three year olds and 23.3% of year 6 children who had evidence of tooth decay among children living in the most deprived areas of England. It is likely that the percentages in Hull more resemble the figures for children living in the most deprived areas of England rather than the overall figure for England.

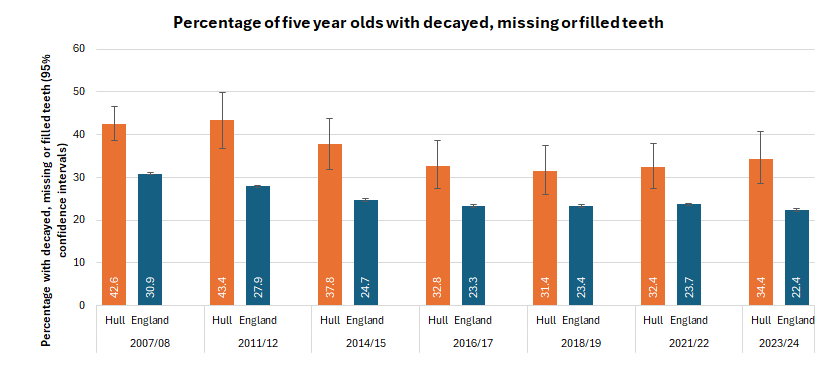

- In 2023/24, over one-third (34.4%) of five year olds in Hull who were surveyed had visually obvious dental decay (that is, any decayed, missing or filled teeth) compared to fewer than a quarter (22.4%) of children in England. his difference is statistically significant. Whilst the percentage has decreased in Hull from 42.6% in 2007/08 to a low of 31.4% in 2018/19, the percentage has increased by three percentage points in Hull in the last five years.

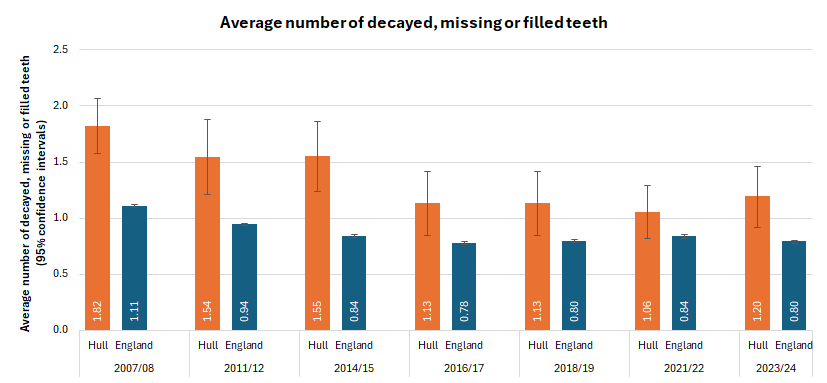

- Among five year olds in Hull for 2023/24, children had an average of 1.2 teeth that were decayed, missing or filled compared to 0.8 teeth in England. This difference is statistically significant. Whilst this is a reduction since 2014/15 when it was an average of 1.6 teeth, the average has increased in recent years (1.13 teeth in both 2016/17 and 2017/18 and 1.06 in 2021/22). Furthermore, the average of 1.2 teeth is made up of an average of 1.1 untreated dentinally decayed teeth and 0.1 filled teeth which suggests relatively high levels of tooth decay that is not treated (an average of 0.6 untreated dentinally decayed teeth, 0.1 missing teeth and 0.1 filled teeth for England).

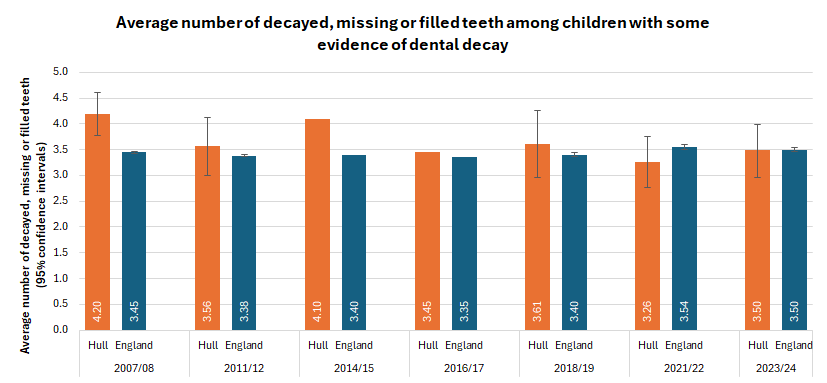

- Among the children that did have some evidence of dental decay (the 34.4% in Hull and the 22.4% in England), the average number of teeth that were decayed, missing or filled was 3.5 teeth for both Hull and England. It was 4.1 teeth in 2014/15, so there has been a reduction since then, but there has some variation since then (3.45 in 2016/17, 3.61 in 2018/19 and 3.26 in 2021/22).

- The percentage of five year olds with substantial plaque has increased from 0.7% in 2015/16 and 0.9% in 2016/17 to 3.5% in 2018/19 and 4.7% in 2021/22, but has decreased in the most recent survey 2023/24 to 2.9%.

- The Care Index and Extraction Index measure the percentage of children with filled teeth (Care Index) and extracted missing teeth (Extraction Index) as a percentage of all children with visually obvious dental decay (any decayed, missing or filled teeth).

- The Care Index has been variable over the course of the surveys since 2007/08. It was lowest at 3.1% in 2007/08 but increased to a high of 17.4% in 2014/15. The latest Care Index if 5.6% which is around half that of England (10.5%).

- The Extraction Index has decreased between 2018/19 and 2023/24 from 14.8% to 1.8%. The latest Extraction Index for England is much higher at 8.1%.

- The relatively low current Care and Extraction Indices suggests that children with dental decay are not seeking treatment (and having decayed teeth filled or extracted). However, in the case of missing teeth it could potential mean that there are differences in the way treatment is undertaken (e.g. teeth not extracted if there is dental decay but dealt with in a different manner). Taking both reductions together though, it does suggest that the percentage of children being treated is lower suggesting that (parents of) children with dental decay are not seeking help which could be associated with the lack of access or perceived lack of access to NHS dental care.

- The rates of tooth extraction for dental decay are more than three times higher for the most deprived fifth of areas of England compared to the least deprived fifth of areas of England (394 versus 117 extractions per 100,000 population), and more than half of Hull’s children live in the most deprived fifth of areas of England. Despite the substantial higher levels of deprivation and high levels of tooth decay in Hull, there were fewer hospital admissions for tooth extractions for dental decay among children and young people aged 0-19 years in hospital that involved general anaesthetic compared to England (110 versus 229 extractions per 100,000 population). In 2023/24, among Hull children aged 0-19 years, there were 160 extractions in total with 75 extractions recorded with a primary diagnosis of caries. However, it is felt that the data might not properly reflect Hull’s position fully. The reason for this is unknown but it is possibly that tooth extractions are occurring within specialist dental services in the community rather than in the hospital. It is also possible that fewer children are seeking help if they have problems with their teeth.

The Population Affected – Why Is It Important?

Cavities, also called tooth decay or caries, are caused by a combination of factors, including bacteria in the mouth, frequent snacking, sugary drinks and not cleaning your teeth well. Dental plaque is a colourless, sticky film that covers the surface of the teeth made up of bacteria, food particles and saliva. If teeth are not cleaned properly, dental plaque can build up. It can also harden to form tartar, and the presence of tartar can protect bacteria making bacteria more difficult to remove. Tooth enamel is mostly made up of minerals, and the initial stage of tooth decay is when the enamel protecting the tooth loses its minerals due to the acids within plaque bacteria. If the enamel is weakened, small holes or cavities or caries can form. The next layer of the tooth under the enamel is dentin and this is softer than enamel, and tooth decay can progress at a faster rate when it reaches the dentin. Dentin also contains the tubes that lead to the nerves of the tooth, and because of this when dentin is affected by tooth decay, sensitivity to hot or cold foods or drinks can result. Pulp is the inner most layer of the tooth containing the nerves and blood vessels that help keep a tooth healthy. When damage to the pulp happens, it may become irritated and start to swell, and this can cause pain due to pressure on the nerves as there is no space for the swelling. As tooth decay advances into the pulp, bacteria can invade and cause an infection, increasing inflammation in the tooth and can lead to a pocket of pus forming at the bottom of the tooth called an abscess. Tooth abscesses can cause severe pain.

Poor dental health impacts not just on the individual’s health but also their wellbeing and that of their family. Children who have toothache or who need treatment may have pain, infections and difficulties with eating, sleeping and socialising.

Poor dental health among children can affect speech, learning to talk and smiling, and as a result can have huge consequences on self-esteem and confidence. There are also associations with poor dental health and other problems such as nutritional deficiencies.

Nationally, a quarter of five year-olds have tooth decay. Children who have toothache or who need treatment may have to be absent from school and parents may also have to take time off work to take their children to a dentist or to hospital.

Oral health is therefore an important aspect of a child’s overall health status and of their school readiness.

The dmft index is a commonly used indicator of tooth decay and treatment experience. It is obtained by calculating the average number of decayed (d), missing due to decay (m) and filled due to decay (f) teeth (t) in a population. In five-year-old children, this score will be for the first (primary) teeth and is recorded as dmft. In older children, it reports on adult teeth and is given in upper case (DMFT). The average dmft/DMFT is the average number of decayed, missing of filled teeth and is used as a measure of the severity of tooth decay experience in a population.

The total number of teeth affected (in terms of decayed, missing or filled teeth) is also quoted in the children’s surveys as well as the number of teeth affected among those that have some evidence of dental decay, missing or filled teeth.

Dental caries or dental decay is the top most common reason for hospital admission among 5-9 year olds in England with 19,560 hospital episodes in 2022/23 (substantially higher than the next highest at 11,306 for acute tonsillitis). For children and young people aged 0-19 years, the total cost for all tooth extractions was £64.3 million in 2022/23 which included £40.7 million for tooth extractions due to tooth decay. Decay-related tooth extraction rates for 2022/23 were 234 per 100,000 population aged 0-19 years for England, but 381 per 100,000 population for children and young people living in the most deprived fifth of areas of England compared to 109 per 100,000 population for children and young people living in the least deprived fifth of areas of England.

The Hull Picture

Number of NHS Dentists in Hull

The number of dentists in Hull providing some NHS activity has decreased in the last few years in Hull, but are still similar to England for 2023/24 with 44 dentists per 100,000 resident population compared to 43 for England.

It is not known if the decrease represents a reduction in dentists overall or a reduction in the number of dentists providing some NHS care (with some dentists changing from offering some NHS care to offering an entirely private service).

| Year | Total dentists | Population per dentist | Dentists per 100,000 resident population |

| 2019/20 | 134 | 1,939 | 52 |

| 2020/21 | 141 | 1,838 | 54 |

| 2021/22 | 132 | 2,019 | 50 |

| 2022/23 | 127 | 2,117 | 47 |

| 2023/24 | 119 | 2,259 | 44 |

However, it should be noted that the rates are given out of Hull’s resident population and this could be potentially misleading. It is not known how many residents of neighbouring East Riding of Yorkshire use dental services in Hull, but it is likely that a sizeable proportion do so. The fact that there are 30 dentists per 100,000 population in East Riding of Yorkshire who provided some NHS activity for 2023/24 lends support to this view. However, this is counterbalanced with the likelihood that there might be more dentists in East Riding of Yorkshire who are entirely private and register no NHS dental activity. Due to Hull’s increased deprivation relative to both England and East Riding of Yorkshire, it is likely that there are fewer (solely) private dentists in Hull.

The national figures above are given as the number of dentists who undertook at least some NHS work during the financial year, but not the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) posts so it is possible that there are differences in the number of hours worked or the number of people seen for each dentist. However, the above figures do give a guide as to the number of dentists working in each local area who are providing some NHS dental care.

Time Since Last Dental Appointment

National information is available on the percentage of children who have attended a dental appointment in the last year for each local authority. The numerator is the number attending a dental appointment for dental practices within the local authority boundary, but the denominator is the estimated resident population for that local authority. In Hull, it is highly likely that East Riding of Yorkshire residents are registered with Hull dentists and are included in the numerator. However, they are not included in the denominator. Around 8% of all patients registered with Hull general practices (GPs) live in East Riding of Yorkshire (around 25,000 patients in total), and it is possible that a similar pattern exists with regard to cross-boundary flows in dentistry. In the national dataset, 62,209 children aged under 18 years had attended a dental appointment in the last year during 2023/24. With an estimated resident population of 37,573 children aged under 18 years, this gives a percentage of 61.5% as quoted in the national dentistry dataset. If it is assumed that 3,006 of the 61,075 dental attendees live in East Riding of Yorkshire (8%) and 34,567 live in Hull, then this would give an ‘adjusted’ estimate of 56.6% for the percentage of under 18s in Hull attending a dental appointment in the last year. With the adjustment, this percentage is similar to England at 55.4%. The percentage for East Riding of Yorkshire is 52.1% in the national dataset, but would be 56.9% if the same adjustment was applied. The number of dentists per 100,000 population mentioned above also lends support to the view that East Riding of Yorkshire residents are registered with Hull dental practices, however, it is also recognised that people in East Riding of Yorkshire will be more likely to be registered for dental care privately.

Dental Decay Recorded From National Surveys

There have been national Oral Health Surveys among children undertaken previously where results are presented at local authority level, but only the survey among five year olds is regularly completed (generally every two years). Not all local authorities participate for various reasons although the likely major reason is due to lack of finances and staff time.

The most recent survey involving three year olds was completed during the 2019/20 academic year, and the results were published by Public Health England in 2020 (now Office for Health Improvement & Disparities) in their Oral Health Survey of Three Year Olds 2020 report. The most recent survey involving children in school year 6 (aged 10-11 years) occurred during the 2022/23 academic year, and the results were published by the Office for Health Improvement & Disparities in their Oral Health Survey of Children in Year 6, 2023 report. Hull did not participate in either of these surveys, but a brief summary of the results for England overall are presented which may give an indication of tooth decay among three year olds and year 6 children. Half of Hull’s population live in areas that are the most deprived fifth of England, so it is likely that the higher prevalence of dental decay among children living in the most deprived areas of England better reflects the situation in Hull rather than the overall figures presented.

Oral Health Survey of Three Year Olds – Results for England

Across England, 19,479 three year olds participated in the survey in 2019/20 and 10.7% already had experience of dental decay despite having had their back teeth for just one or two years. Among the 10.7% of children with experience of tooth decay, each had on average 2.9 teeth affected (by three years of age, children normally have all 20 primary teeth). Children living in the most deprived areas of England were almost three times more likely to have experience of dental decay compared to children living in the least deprived areas (16.6% versus 5.9%). Children from other minority ethnic groups (20.9%) and Asian and Asian British children (18.4%) were more likely to have dental decay compared to other groups. In 2013, when the only previous survey of three year olds was completed, 11.7% had experience of dental decay.

Oral Health Survey of 10-11 Year Olds – Results for England

Across England, 53,073 children in school year 6 who were aged 10-11 years participated in the survey in the 2022/23 academic year. Overall, 16.2% had evidence of dental decay, each with an average of 1.8 teeth affected. There was also a strong association with deprivation among the year 6 children. Almost one-quarter (23.3%) of children living in the most deprived fifth of areas of England had evidence of dental decay compared to one in eight (12.6%) of children living in the least deprived fifth of areas of England. Children from other minority ethnic groups (22.2%) were more likely to have dental decay compared to other groups, and whilst Asian and Asian British children (17.8%) had the second highest percentage of dental decay, the percentage was not drastically different to the overall figure of 16.2%. Girls were more likely to have dental decay (16.9%) compared to boys (15.3%).

Oral Health Survey of Five Year Olds – Results for Hull

There have been oral health surveys of five year olds completed for a number of years generally once every two years, although the one survey due during the COVID-19 pandemic was delayed a year. Not all local authorities participate in the survey.

The Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips gives a summary measure of the percentage of five year olds with experience of visually obvious dentinal decay.

More detailed information is available from the national datasets, and further details are presented below.

Among five year olds surveyed in Hull in 2023/24, just over one-third (34.4%) had one or more decayed, missing of filled teeth in Hull compared to just over one-fifth in England (22.4%).

Compared with benchmark

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | North Yorkshire UA | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Percentage of 5 year olds with experience of visually obvious dental decay (Persons 5 yrs) | 2023/24 | 22.4 | 27.5 | 34.4 | - | 30.7 | 25.4 | - | - | 30.2 | 25.4 | 23.5 | 28.5 | 37.1 | - | - | 21.9 | - |

| Indicator | Period | England | Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical) | Kingston upon Hull | East Riding of Yorkshire | North East Lincolnshire | North Lincolnshire | York | North Yorkshire UA | Barnsley | Doncaster | Rotherham | Sheffield | Bradford | Calderdale | Kirklees | Leeds | Wakefield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Percentage of 5 year olds with experience of visually obvious dental decay (Persons 5 yrs) | 2023/24 | 22.4 | 27.5 | 34.4 | - | 30.7 | 25.4 | - | - | 30.2 | 25.4 | 23.5 | 28.5 | 37.1 | - | - | 21.9 | - |

Whilst the percentage of five year olds with visually obvious dental decay is considerably higher in Hull than England, the percentage has fallen sharply in Hull between 2007/08 and 2023/24 by 19% from 42.6% to 34.4%. However, the percentage in England has reduced by a greater amount (by 28%) so the inequalities gap between Hull and England has increased.

Despite the overall decrease from 2007/08, the percentage in Hull has increased in the last few years from 31.4% in 2018/19 to 34.4% in 2023/24. It is not possible to say why this might have occurred, but it could be that the COVID-19 pandemic and lack of access to dentistry, in combination with more recent national and local problems with access to NHS dental services has compounded the levels of tooth decay in Hull. This has not been the case as clearly at a national or regional level, but it is possible that access to NHS dental services are more of a problem in more deprived areas like Hull compared to other areas where private dental services are more accessible.

Compared with benchmark

Percentage of 5 year olds with experience of visually obvious dental decay (Persons 5 yrs)

|

Period

|

Kingston upon Hull |

Yorkshire and the Humber region (statistical)

|

England

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Count

|

Value

|

95%

Lower CI |

95%

Upper CI |

||||

| 2007/08 | • | - | 42.6% | 38.6% | 46.6% | 38.7% | 30.9% |

| 2011/12 | • | - | 43.4% | 36.7% | 50.0% | 33.6% | 27.9% |

| 2014/15 | • | - | 37.8% | 31.9% | 43.8% | 28.5% | 24.7% |

| 2016/17 | • | - | 32.8% | 27.4% | 38.7% | 30.4% | 23.3% |

| 2018/19 | • | - | 31.4% | 26.0% | 37.5% | 28.7% | 23.4% |

| 2021/22 | • | - | 32.4% | 27.3% | 37.8% | 27.0% | 23.7% |

| 2023/24 | • | - | 34.4% | 28.6% | 40.7% | 27.5% | 22.4% |

Source: Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, National Dental Epidemiology Programme

Survey Completed in 2018/19

Examining the more detailed national reports and datasets for the 2018/19 survey, it was noted that 245 five year olds were examined in Hull (approximately 70% of the sample drawn which was higher than England at 61%).

Overall, 31.4% of five year olds had experience of visually obvious dentinal decay compared to 23.4% for England. On average, children in Hull had 1.13 teeth that were decayed (0.89 or 79%), missing (0.17 or 15%) or filled (0.07 or 7%) compared to 0.80 for England (0.63 or 79% decayed, 0.09 or 11% missing, and 0.08 or 10% filled). Thus children in Hull had more teeth that were decayed, missing or filled overall, but also more teeth that were missing relative to filled. Among the children that had at least one decayed, missing or filled teeth, on average, these children had 3.6 decayed, missing or filled teeth compared to 3.4 for England. In Hull, 3.5% of five year olds had substantial plaque compared to 1.2% in England, 1.7% had oral sepsis (1.0% in England) and 7.7% had incisor caries (5.2% in England).

Survey Completed in 2021/22

The national dental survey was also completed in 2022 among five years olds. In Hull, it was estimated that there were 3,353 five year olds living in the city and 300 took part in the survey representing 8.9% of all five year olds.

In 2021/22, 32.4% of five year olds had experience of visually obvious dentinal decay compared to 23.7% for England. This equates to 97 out of the 300 five year olds participating in the survey in Hull. Across all five year olds, the average number of dentinally decayed teeth, missing teeth that had been extracted due to dental decay and filled teeth was 1.06 which was higher than England at 0.84. This was made up of 0.90 decayed teeth, 0.04 missing teeth and 0.12 filled teeth.

Among the children that did have decayed, missing or filled teeth, the average number of decayed, missing or filled teeth was 3.3 teeth (comprising 2.8 decayed teeth and 0.1 filled teeth).

Three in ten of five year olds had one or more teeth that was dentinally decayed and among those that did, the average number of teeth that was affected was 2.90 teeth. The percentage was much higher than the England average where 21.8% had one or more teeth that was dentinally decayed, although among those children in England that were in this situation the average number of teeth affected was slightly higher at 3.32 teeth.

Only 1.8% of children had one or more teeth that had been extracted due to tooth decay, and among these children who did have missing teeth, the average number of teeth that had been extracted was 2.90 teeth.

Overall, 4.7% of children in Hull had substantial amounts of plaque which was higher than England (3.3%), a much higher percentage of children in Hull had enamel decay which is an early stage of decay who would ordinarily be counted as being free of obvious decay (23.3% versus 13.6%), and children in Hull were also more likely to have other oral conditions resulted from untreated caries (visible pulp, ulceration, fistula or abscess) compared to England (3.6% versus 2.0%). With 300 Hull children participating in the survey, this equates to around 14 children with substantial amounts of plaque, 70 children with enamel decay, and 11 children with visible pulp, ulceration, fistula or abscess from untreated caries. It is not possible to sum these numbers as it is possible that some of the same children are included in these three groups.

Slightly fewer children in Hull had incisor caries compared to England (6.1% versus 6.5%) and a higher percentage of children in Hull had decayed teeth where there was pulp evident (6.5% versus 4.1%).

One in nine children in Hull (11.4%) who had dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth had been treated through fillings which was higher than England (7.4%), although in Hull fewer of these children had been treated through having teeth extracted due to the dental decay compared to England (3.4% versus 6.4%).

Survey Completed in 2023/24

Based on the Office for National Statistics mid-year 2022 population estimates, 3,367 five year olds live in Hull. There were 235 who participated in the 2023/24 representing around 7.0% of all five year olds in Hull which was lower than England (12.6%).

Among all children examined, the average number of teeth that were decayed, missing or filled was 1.2 teeth for Hull children compared to 0.8 teeth for England with the majority of these decayed (very few were missing or filled).

Over one-third (34.4%) of the five year olds in Hull examined had at least one decayed, missing or filled teeth compared to under one-quarter (22.4%) for England. This difference between Hull and England was statistically significant (p=0.000012 – see Statistical Testing and Statistical Significance in the Glossary). Among these children with evidence of decayed, missing or filled teeth, the average number of teeth affected was 3.5 teeth in Hull which was the same as England.

Over one-third (34.4%) of children in Hull had one or more decayed teeth which was the same as the percentage with at least one decayed, missing or filled teeth. However, in England, the percentage was lower at 19.8%. Presumably it was all the same children in Hull, but this suggests for England, some of the children with existing filled or missing teeth did not also have decayed teeth, but this was not the case in Hull.

Twice as many children in England had missing teeth which had been extracted due to tooth decay (1.8%) compared to Hull children (0.7%). Children in Hull have much higher levels of dental decay and this suggests that children in Hull are less likely to seek help or see a dentist as missing or filled teeth would only result from a dental visit or from seeking help from elsewhere. This is supported by the Care Index and Extraction Index. These measure the percentages of children who have filled or missing teeth respectively among those who have some evidence of decayed, missing or filled teeth. In Hull, one in twenty (5.6%) of children had filled teeth among the children that had some evidence of decayed, missing or filled teeth compared to one in ten (10.5%) for England. So it would appear that children with decayed, missing or filled teeth in England were twice as likely to have at least one filled tooth compared to children in Hull. However, this was even more extreme for missing teeth extracted due to dental decay where children in England were 4.5 times more likely to have teeth extracted due to dental decay (8.1% versus 1.8%).

Children in Hull were more likely to have any plaque, visible pulp, ulceration, fistula or abscess, advanced decay, incisor decay and enamel decay compared to England, but slightly lower percentages with substantial plaque.

Among the children with evidence of decayed, missing or filled teeth, over four in ten (41.5%) in Hull had enamel and/or any dentinal decay compared to just over one-quarter (26.9%) for England.

Among children with no evidence of decayed, missing or filled teeth, 7.1% of children in Hull had enamel and/or any dentinal decay compared to 4.6% for England.

| Dental measure | Hull % | England % |

| Average number of dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Average number of untreated dentinally decayed teeth | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| Average number of missing teeth (extracted due to dental decay) | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Average number of filled teeth | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Percentage of children with dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth | 34.4 | 22.4 |

| Average number of dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth among those with some dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Average number of dentinally decayed teeth among those with some dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth | 3.2 | 2.9 |

| Average number of filled teeth among those with some dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Percentage of children with dentinally decayed teeth | 34.4 | 19.8 |

| Average number of dentinally decayed teeth among those with some dentinally decayed teeth | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Percentage of children with missing teeth (extracted due to dental decay) | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| Average number of missing teeth among those with some missing teeth (extracted due to dental decay) | 3.0 | 3.5 |

| Percentage of children with substantial amounts of plaque | 2.9 | 3.3 |

| Percentage of children with either visible pulp, ulceration, fistula or abscess | 4.6 | 1.8 |

| Percentage of children with advanced decay | 7.1 | 3.7 |

| Percentage of children with incisor decay | 11.1 | 6.0 |

| Percentage of children with enamel decay | 14.6 | 11.0 |

| Percentage of children with enamel and/or any dentinal decay among those with some dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth | 41.5 | 26.9 |

| Percentage of children with enamel and/or any dentinal decay among those with no dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth | 7.1 | 4.6 |

| Percentage of children with any plaque | 28.5 | 22.1 |

| Care Index (percentage of dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth that have been treated / filled) | 5.6 | 10.5 |

| Extraction Index (percentage of dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth that have been extracted due to decay) | 1.8 | 8.1 |

Trends Over Time

It is possible to compare the results of the 2023/24 survey with previous surveys. Standard dental abbreviations have been used in the table with small letters denoting deciduous teeth only. Dentinally decayed is noted as d3, missing due to dental decay is noted by m, and filled teeth by f, with teeth denoted by t. The majority of the measures have been collected throughout all surveys but there have been more measures of dental decay recorded in the more recent surveys.

In 2014/15, 37.8% of Hull’s five year olds had one or more missing, filled or decayed teeth compared to 34.4% in 2023/24. Whilst that represents a reduction, the reduction is not statistically significant (p=0.43 – see Statistical Testing and Statistical Significance in the Glossary). For every survey (2014/15, 2016/17, 2018/19, 2020/21 and 2023/24), there was a statistically significant difference in the percentage of children with missing, filled or decayed teeth between Hull and England with children in Hull having a higher percentage compared to England.

The following summary findings were noted:

- The average number of dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth has substantially reduced among five year olds in Hull from 1.55 teeth in 2014/15 to 1.06 teeth in 2021/22 but increased to 1.2 teeth for 2023/24.

- The average number of decayed teeth and missing teeth over this time was 1.2 teeth in 2014/15 and whilst this decreased to 0.87 teeth in 2016/17, it has gradually increased to 1.1 teeth in 2023/24.

- In 2014/15, 37.8% of five year olds had one or more decayed, missing or filled teeth, and whilst this reduced to 31.4% for 2018/19, the percentage has subsequently increased to 34.4% for 2023/24.

- Among those who did have one or more decayed, missing or filled teeth, the number of teeth affected has also reduced over time from 4.10 teeth in 2014/15 to 3.26 teeth in 2021/22, but this has also increased in the last year to 3.5 teeth.

- The percentage of children with at least one decayed tooth has remained relatively constant between 28% and 31% across the four surveys 2014/15 to 2021/22, but has increased to 34.4% for 2023/24.

- The percentage of children with at least one missing tooth extracted due to decay has decreased over time from 2.8% in 2014/15 and 4.4% in 2016/17 to 0.7% in 2023/24. However, the number of children with missing teeth due to dental decay is small, so there is considerably year-on-year variability and the results should be treated cautiously. Furthermore, it is possible that fewer children have teeth extracted as they are not presenting at dentists or hospital.

- The percentage of children with substantial plaque has increased substantially with fewer than 1% for the 2014/15 to 4.7% in 2021/22, but has decreased in the last year to 2.9%.

- Fewer children had incisor cavies and the percentage more than halved between 2014/15 and 2021/22. The percentage of children with decay to an extent that the pulp was visible has also reduced from 8.7% in 2016/17 to 6.5% in 2021/22.

- In 2014/15, 17.4% of all children with at least one tooth that was decayed, missing or filled, had filled teeth. This was considerably lower for subsequent years, and was 5.6% for the most recent year 2023/24. This means a lower percentage of children have filled teeth among those with decayed, missing or filled teeth, which suggests that children are not been treated for dental decay which could be related to problems accessing dentistry.

- In 2018/19, 14.8% of children at least one tooth that was decayed, missing or filled, had missing teeth, but this was much lower at 1.8% for 2023/24. This suggests that children are not having teeth extracted as frequently when they have dental decay. This could be because of other treatments being available, but it could also be because children are not accessing treatment for dental decay.

| Dental measure | 2007/08 | 2011/12 | 2014/15 | 2016/17 | 2018/19 | 2021/22 | 2023/24 |

| Number of children surveyed | 573 | 219 | 251 | 261 | 245 | 300 | 235 |

| Average d3mft | 1.82 | 1.54 | 1.55 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.2 |

| Average d3t | 1.58 | 1.27 | 1.20 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 1.1 |

| Average mt | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.0 |

| d3mft > 0 (%) | 42.6 | 43.4 | 37.8 | 32.8 | 31.4 | 32.4 | 34.4 |

| Average d3mft (d3mft > 0) | 4.2 | 3.56 | 4.10 | 3.45 | 3.61 | 3.26 | 3.5 |

| d3t > 0 (%) | 40.3 | 39.2 | 31.6 | 28.3 | 28.0 | 30.9 | 34.4 |

| Average d3t (d3t > 0) | 3.88 | 3.24 | 3.78 | 3.09 | 3.19 | 2.90 | 3.2 |

| mt > 0 (%) | 3.5 | 2.8 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 0.7 | |

| Average mt (mt > 0) | 3.07 | 3.49 | 4.99 | 2.00 | 3.0 | ||

| Substantial plaque (%) | 0.7 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 4.7 | 2.9 | ||

| Incisor cavies (%) | 12.7 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 6.1 | |||

| Decay with pulp (%) | 8.7 | 8.3 | 6.5 | ||||

| Care Index (%) | 3.1 | 10.1 | 17.4 | 9.2 | 6.5 | 11.4 | 5.6 |

| Extraction Index (%) | 14.8 | 3.4 | 1.8 |

| Dental measure | Change from earliest date* to 2023/24 (%) | Change from 2021/22 to 2023/24 (%) |

| Average d3mft | -34.1 | 13.7 |

| Average d3t | -30.5 | 22.4 |

| Average mt | -100 | -100 |

| d3mft > 0 (%) | +78.0 | -17.1 |

| Average d3mft (d3mft > 0) | -19.2 | 6.3 |

| d3t > 0 (%) | -14.6 | 7.3 |

| Average d3t (d3t > 0) | -17.5 | 10.2 |

| mt > 0 (%) | -80.0 | -61.1 |

| Average mt (mt > 0) | -2.3 | +50.0 |

| Substantial plaque (%) | +289 | -37.8 |

| Care Index (%) | +81.6 | -50.0 |

| Extraction Index (%) | -87.9 | -47.2 |

*Change is generally from 2007/08 but not all indicators measured for this survey year, and if they are missing for 2007/08 the comparison is made with the next period where that indicator was measured.

Despite around 7% (and 9% for latest year) of all five year olds who live in Hull participating in the survey, the numbers are relatively small overall, and as a result there is uncertainty around the levels of dental decay in Hull among five year olds (see Small Numbers for more information). To obtain some indication of the degree of uncertainty around these measures of dental decay, it is possible to calculate confidence intervals. These give a range of values where the true value is likely to fall, and if the confidence intervals are wide this denotes that there is more uncertainty around the figures produced from the survey (see Confidence Intervals for more information).

The trends over time in the percentage of children who have one or more dentinally decayed, missing or filled teeth together with 95% confidence intervals is given below. With no overlap in confidence intervals between Hull and England for each time period, there is a statistically significant difference between Hull and England (see Statistical Testing and Statistical Significance for more information). For the latest year, the statistically significance level is small denoting strong evidence of a difference (p=0.000012).

If comparing the most recent period 2023/24 for Hull, there is a statistically significant difference (improvement) since 2007/08 (p=0.032), but there is no statistically significant difference between 2023/24 and 2011/12 (p=0.051), 2014/15 (p=0.43), 2016/17 (p=0.71), 2018/19 (p=0.48) or 2021/22 (p=0.60).

In relation to the average number of decayed, missing or filled teeth among all children, there has been an improvement in Hull over time. The difference appears to be statistically significant as there is no overlap in confidence intervals between 2007/08 and 2023/24.

There is a large difference in the average number of decayed, missing or filled teeth between Hull and England for all the surveys.

Among the subset of children who had some evidence of dental decay, the average number of decayed, missing or filled teeth has decreased from highs in 2007/08 and 2014/15, but the latest average number of teeth affected is similar to the other survey years. Furthermore, the difference between Hull and England is much smaller in the majority of the surveys, and for 2023/24, the average number of decayed, missing or filled teeth among the subset of children who had some evidence of dental decay was the same for Hull as it was in England.

Background to Five Year Old Surveys

The Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (previously Public Health England) facilitate and co-ordinate the surveys, but local authority teams commission the surveys locally and liaise with the participating schools. Schools are randomly chosen to take part in the survey, and among those that agree to take part, a list of all five year olds is drawn up at the selected schools. For small schools, every five year old is invited to participate and in larger schools it is one in every two, or one in every three or four children. Schools can refuse to take part and if schools in more deprived areas refuse to take part this could bias the findings. Furthermore, parents can refuse permission to participate and/or the children themselves can refuse to take part, and it is likely that five year olds with poor dental health or who have not regularly attended a dental appointment will be more likely to not want to participate in the dental examination. This could bias the findings, but in general, it is likely that the findings are reasonably representative of Hull’s five year olds especially in Hull as most schools approached generally agree to take part.

Nevertheless, the total numbers of five year olds taking part is relatively small which does result in some random variation, and wider confidence intervals.

Tooth Extractions Occurring in Hospital

Information is also available on the number of tooth extractions of permanent teeth which occur in hospital under general anaesthetic for those aged 0-19 years (with numbers rounded to the nearest five with counts fewer than eight not presented). The majority of extractions are due to dental decay particularly among younger children.

However, the data should be treated very cautiously as it is unlikely to be complete. The data is only tooth extractions that occurred in hospital under general anaesthetic, and there will be dental services in the community where tooth extractions occur. The figures in Hull presented below are likely to be an underestimate of the total number of tooth extractions among 0-19 year olds in Hull given Hull’s high levels of deprivation and poor dental health as illustrated in the oral health survey among five year olds.

There were 160 tooth extractions that occurred in hospital under general anaesthetic in 2023/24 among Hull children aged 0-19 years with 10 among 0-4s, 25 among 5-9s, 55 among 10-14s and 70 among 15-19 year olds. This gave an extraction rate of 235 extractions per 100,000 population compared to 368 extractions per 100,000 population for England. Just under half (47%) of all tooth extractions in Hull were due to caries compared to 62% for England.

Across England, there was a strong association with the rate of tooth extractions per 100,000 population by deprivation. Children living in the most deprived fifth of areas of England had an extraction rate of 394 per 100,000 population compared to 117 per 100,000 population for children living in the least deprived fifth of areas of England. It is likely that a similar pattern with deprivation exists in Hull, and as mentioned above, the figures in the following table are likely to underestimate the number of tooth extractions occurring in Hull’s children.

| Age | Hull N (all) | Hull rate (all) | Hull N (caries) | Hull rate (caries) | England rate (all) | England rate (caries) |

| 0-4 | 10 | 17 | * | * | 153 | 125 |

| 5-9 | 25 | 147 | 20 | 117 | 605 | 528 |

| 10-14 | 55 | 310 | 30 | 169 | 388 | 195 |

| 15-19 | 70 | 408 | 15 | 87 | 307 | 65 |

| 0-19 | 160 | 235 | 75 | 110 | 368 | 229 |

NOTE that the data is likely to be incomplete as it only includes teeth extractions that occurred in hospital and not those that occurred in the community.

* Numbers and rate not given as count is less than eight and suppressed.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic, Cost of Living Crisis and Access to Dental Surgeries

Access to routine care and emergency treatment from March 2020 to the end of 2021 was severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. To limit COVID-19 transmissions, dental practices were instructed to close and cease all routine dental care from the 25 March 2020 to 8 June 2020. This included all routine dental care including orthodontics, all aerosol generating procedures, offering patients with urgent needs appropriate advice and prescriptions over the telephone, and ceasing all face-to-face urgent care. However, in reality, many practices did not offer routine check-up appointments again until Spring / Summer 2021. Routine check-ups will pick up dental problems early, and it is likely that with no routine check-ups the numbers of people requiring further additional treatment or more severe treatment will increase. This will be compounded as most dental surgeries when they did open had a backlog of patients requiring check-ups and treatment.

It is possible that the cost of living crisis has further impacted adversely on oral health. With an increasing number of people having problems affording to heat their home and provide adequate food for their family, it is likely that there will be more people not buying toothpaste or new toothbrushes, and not accessing dental health care. Dental health care for adults – even on the NHS – incurs a cost, and despite dental health care being free for children, it may incur additional costs in terms of taking time off work to accompany children and travel costs.

From anecdotal evidence, access to dental care can be difficult with patients not being able to access care if their dentist leaves the profession and dental surgery struggles to recruit a replacement, other people have been left without a dentist if their dentist or dental surgery changes from providing NHS care to entirely private (and they chose not to remain with that dentist and pay privately), and there are people who are not registered with a dentist at all, or who are on long waiting lists to register with an NHS dental practice.

Strategic Need and Service Provision

Hull’s Oral Health Plan – Improving Oral Health for Local People – was produced through partnership working and underpins the local dental commissioning and oral health improvement strategies to ensure that local people’s oral health needs are met. There were five workstreams and activities described falling under:

- Creating a supportive environment for health;

- Re-orientating health services;

- Developing personal skills;

- Strengthening community action; and

- Building healthy public policy.

National strategies, priorities and evidence-based guidance include:

- To ensure that people have appropriate levels of fluoride (whether this is through toothpaste, fluoride varnishes, or fluoridation of the water).

- To ensure that everyone who needs it has access to good NHS dental services, and that sufficient information is provided to residents to allow them to understand the value of having regular check-ups.

- Support for prevention-orientated NHS dental services. It is necessary to explore equity of access and barriers to NHS dental services particularly for people from more vulnerable groups.

Existing work commissioned by the Integrated Care Board (ICB) and Hull city council include:

- Flexible commissioning contracts commissioned by the ICB which emphasise prevention in practice.

- ICB-commissioned primary care dental access initiatives for those experiencing homelessness, and urgent dental access sessions within Hull, to increase access to dental services.

- ICB are piloting a level 2 paediatric primary care service model to support workforce development and utilisation of skill-mix. This is significantly improving Community Dental Service waiting times for those children requiring consultant-led care.

- Hull city council commissions an oral health promotion service. This includes supervised toothbrushing scheme to the most deprived areas, smoking cessation training to dental providers, workforce training (for those in care homes and early years), health visitor Brush for Life toothbrush and toothpaste packs.

There are other specific groups that are much more likely to have poorer oral health and access to dental services, and it is necessary to improve oral health and access to services for children in inclusion health groups and children in inclusion health groups.

Many existing public health initiatives link with oral health, and this should be considered in relation to improving oral health and physical health in general through opportunities related to delivering services provided by local and national government and the NHS. However, it is recognised that many service are already not provided or stretched due to the current financial setting, so it may not be possible to take advantage of such opportunities. Such links include promotion and access to nutritious food and reducing sugar intake, and promotion and improved access to, and addressing vaccine hesitancy in relation to the human papillomarvirus (HPV) vaccination which links to oral cancer.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its resulting backlogs, cost of living crisis, and access to NHS dental care, it is likely oral health has deteriorated in the last 3-4 years, and furthermore this will impact on inclusion health groups to a greater extent.

Resources

Healthline. The stages of tooth decay: what they look like. https://www.healthline.com/health/dental-and-oral-health/tooth-decay-stages

The Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (formerly Public Health England) Health Matters blog on oral health in children

The Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Fingertips: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/

NHS Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-dental-statistics

Oral health survey of 5-year-old children 2019: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/oral-health-survey-of-5-year-old-children-2019

Oral health survey of 5 year old children 2022: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/oral-health-survey-of-5-year-old-children-2022

Oral health survey of 5 year old children 2024: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/oral-health-survey-of-5-year-old-schoolchildren-2024

The Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (formerly Public Health England): Hospital tooth extractions of 0 to 19 year olds. www.gov.uk

UK Government. All Our Health. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/all-our-health-personalised-care-and-population-health#about-all-our-health

UK Government, 2021. Delivering Better Oral Health. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention

The Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (previously Public Health England), 2014. Improving oral health: an evidence-informed toolkit for local authorities for children and young people. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-oral-health-an-evidence-informed-toolkit-for-local-authorities

The Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (previously Public Health England), 2016. Menu of Preventative Interventions. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a8d9697e5274a5e64c54608/Local_health_and_care_planning_menu_of_preventative_interventions_DM_NICE_amends_14.02.18__2_.pdf

The Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (previously Public Health England), 2016. Improving the oral health of children: cost effective commissioning: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-the-oral-health-of-children-cost-effective-commissioning

National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Public Health Guidance 55. Oral health, local authorities and partners. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph55

Updates

This page was last updated / checked on 18 July 2025.

This page is due to be updated / checked in July 2026.